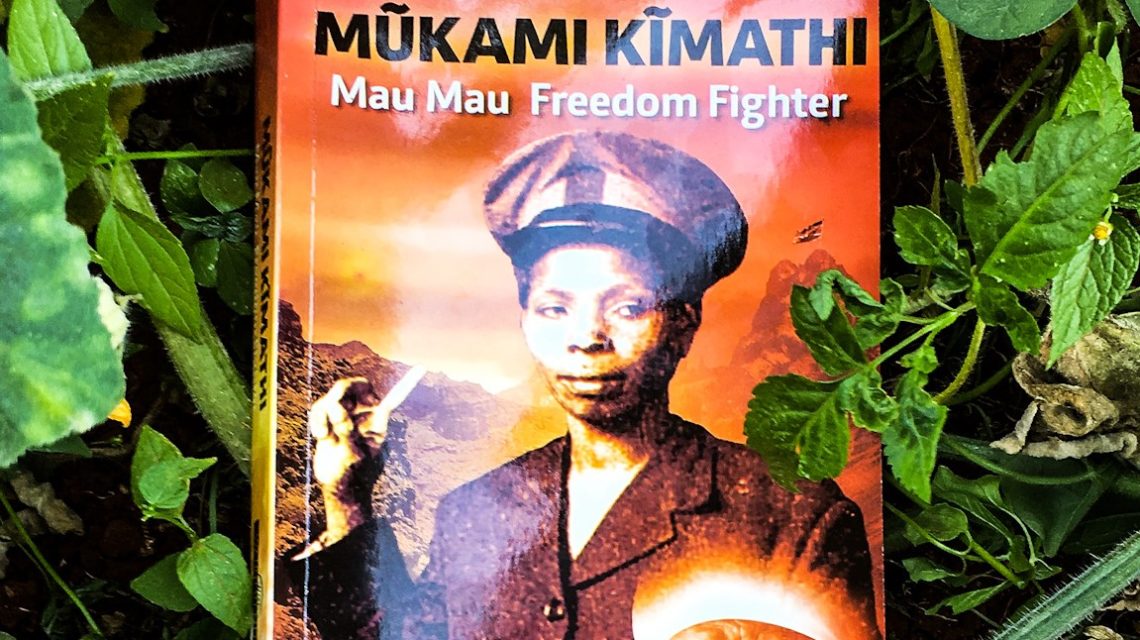

Mũkami Kĩmathi, Mau Mau Freedom Fighter – How Kenyatta and Odinga vied for Mau Mau vote August 18, 2020 – Posted in: Review

For millions of Kenyans, yesterday was just another Sunday. But for Mukami Kimathi and the remnants of the Mau Mau movement that waged the war for independence in the 1950s, it was a special day. Unbeknown to many Kenyans, February 18 marked the day the icon of the independence struggle, Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi, was executed by the colonial government for his role in the Mau Mau war. Yesterday marked the 60th anniversary of Kimathi’s death.

Kamiti Prison

Kimathi died on February 18, 1957. A doctor, K.E Robertson, confirmed Kimathi dead at Kamiti prison after the execution conducted by the then prisons superintendent, a Mr Whitehole. According to an endorsement paper written by Robertson, the former freedom fighter was placed on the gallows at 6am. No one knows where Kimathi was buried and the British Government has remained silent on the matter. As Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga continue to tussle politically, Kimathi’s shadow continues to lurk in the background of Kenya’s longest clash between two political dynasties – the Kenyattas and Odingas.

The role of Kimathi’s widow, Mukami, a Mau Mau war veteran herself, has been immortalised in a book that contains some eye-opening chapters, including how Jomo Kenyatta and Jaramogi Odinga, Kenya’s foremost political protagonists, scrambled for the Mau Mau support during the 1966 ‘little election’. Odinga walked out of the ruling party, Kanu, to form the Kenya People’s Union (KPU). In retaliation, Kanu passed a constitutional amendment that required those who changed party affiliation to resign from Parliament. This led to the 1966 election battle, akin to a subsequent clash between Uhuru and Raila decades later, which left the country deeply polarised. In the book, Mukami Kimathi: Mau Mau Freedom Fighter, penned by Wairimu Nderitu, Kimathi’s widow talks of bitter ideological differences between Kenyatta and his deputy, Jaramogi Odinga, and how each desperately tried to convince her to tell other freedom fighters to support his side.

“Both Kenyatta and Odinga constantly sought me out to for support and to hear my opinion on the Mau Mau position on what was going on in the country,” states Mukami.

War veterans

She points out that as the two titans courted Mau Mau for political support they did little to address the suffering the independence war veterans, given that the organisation was still proscribed by the government they were now leading. “Their differences were increasingly framed in an ethnic lens as Gikuyu versus the Luo and vice versa,” stated Mukami. Mukami blames history for today’s political problems.

Tribal lines

According to Mukami, the British ensured that Kenya would always need her coloniser as a referee in future ethnic differences by ensuring that Kenya’s two founding parties – Kenya African National Union (Kanu) and the Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu) ran along tribal lines. The freedom fighter argues that the colonial master preferred Kadu, then led by Ronald Ngala, with membership drawn mainly from coastal communities. Kanu, on the other hand, drew membership from the Kikuyu and Luo communities.

Feeling betrayed

Both parties were keen to take over the government when the settlers left. According to Mukami, Mau Mau fighters threw their weight behind Kanu, thinking it was the party that would deliver them from misery. Six decades later, remnants of the Mau Mau feel betrayed. According to Mukami, although Kanu wanted the fighters’ support, it was not willing to return the favour. It did not do what many fighters had hoped for: kicking out colonial loyalists, commonly referred to as home guards, from occupied lands. At the very least, the fighters expected to be rewarded for their role in the struggle. This did not happen and the struggle for recognition would haunt the Mau Mau under subsequent regimes. Mukami stops short of declaring that the independence struggle was not won, and that her husband may have died in vain. The white man, she opined, did not leave; he continued reigning through black proxies.

Black proxies

“The pain of imagining that the colonialists would not leave cannot be described,” says Mukami. “Many of the Mau Mau had no land to go back to. It was all gone to home guards, collaborators, and loyalists.”